November 20: National Absurdity Day

Occurring on winter’s cusp, National Absurdity Day is a fantastic way to liven up a ho-hum day. It’s a day to have fun and do crazy, zany, and absurd things. Use the day as an excuse to let out the silly hidden inside you break loose. You can do things you have wanted to do that make absolutely no sense at all, and it will be okay because you will be celebrating this national day. Dye your eyebrows pink, juggle eggs in the Bistro, or lead a meeting while standing on your hands. There’s no limit to the wackiness of this day. Follow your most preposterous whims.

Absurdity, which refers to the illogical, unreasonable or nonsensical has been widely studied and written about. In fiction and humor, the absurd is usually used to make a nuanced point about human behavior. Lewis Carol's Alice in Wonderland is considered to be one of the most well-known works of absurdist literature. Others include Franz Kafka, Saul Bellow, Eugène Ionesco, and Samuel Beckett.

While absurdity in its many forms has been a subject of study since the time of the ancient Greeks, the real philosophy of absurdism began in the 19th century in the mind of the Danish philosopher named Søren Kierkegaard. Its premise is that humans are all searching to find meaning in a meaningless universe. As years passed, this philosophy gained popularity and became the touchstone for a movement in theatre and literature in Europe and North America

right after WWII. In the 1950s and 1960s, the peak of such artistic movements as the Theater of the Absurd and Surrealism gave rise to an entire genre of literature based on nonsequitur behaviors and otherworldly plots. Some say that many writers and film makers were reacting to the threat of nuclear war by including absurdist themes in their works.

The origins of National Absurdity Day are not known. Rather fitting. Whatever the origin, National Absurd Day is an opportunity to embrace a new and freeing philosophy in all our words and deeds, just to see what it’s like to unsubscribe from the order and organization of normal human life for a few hours. This is the day to recall and note some of the entirely off-the-wall and ridiculous things in history, in our country, and in our lives.

November 21: National Gingerbread Cookie Day

National Gingerbread Cookie Day is the perfect time to enjoy gingerbread cookies.

Gingerbread cookies instantly make us feel warm and cozy. Their rich flavor makes you want to keep going back for more. This time of year, gingerbread cookies come in all shapes and sizes — stocking, bells, candy canes — but gingerbread men are the most popular ones (and they’re popular all year round). Whatever form they take, gingerbread cookies are sweet cookies made with a variety of fall spices — including cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, cardamom, and anise — sweetened with molasses, corn syrup, or brown sugar.

Gingerbread has been around for centuries. The Ancient Greeks and Egyptians often used gingerbread for ceremonial purposes. Later, in the 11th century, crusaders brought ginger into Europe from the Middle East. It was in the 16th century that gingerbread figure cookies made their first appearance. Queen Elizabeth I of England asked her staff to make gingerbread figures that looked like the foreign dignitaries and the other guests of honor and later presented them in the likeness of some of her very important guests. In England, gingerbread cookies were also sold around the 17th century in monasteries, pharmacies, and farmers’ markets.

In Germany, in certain places like Nuremberg and Pulsnitz, gingerbread is regarded as an art form. The German version of gingerbread cookies is known as Lebkuchen (a recipe that has been around for over 400 years.) These were often heart-shaped and decorated with names and messages of love written in icing. Gingerbread cookies are also highly regarded as art in Torun in Poland, Tula in Russia, Pest in Hungary, Pardubice, Prague in the Czech Republic, and Lyon in France. Later as years went by, gingerbread tied with ribbons became a popular feature at local fairs and were even exchanged as a token of love.

Now-a-days, gingerbread cookies are popular in many western countries and especially baked around the holiday season. You can make a house, cake, biscuits, or simply cookies, and munch your way through it during the holidays and soak in the warm and spicy flavors.

November 22: National Jukebox Day

National Jukebox Day is the day before every Thanksgiving — November 22 this year. Music is the soundtrack of our lives, and this day celebrates the jukebox, shining some light on the device that brought, and still brings, music into our lives in a special way.

The term “jukebox,” coined in 1937, is thought to have derived from places called “juke houses” or “jook joints,” where, since the early 1900s, people congregated to drink and listen to music. According to vocabulary.com, “Many country and blues bands got their start playing at jukes in the south, although some jukes offer jukeboxes as their only music. You can also call it a ‘juke joint.’ The word juke comes from the Southern US Creole known as Gullah, in which ‘juke’ or ‘joog’ means ‘wicked’ or ‘disorderly.’"

The jukebox has a rich history; the nostalgia it carries is unparalleled. It has been around for era after era of modern music — from jazz to country and blues to rock. Jukeboxes revolutionized music in many ways. With its invention, people could enjoy music in restaurants and bars. Artists found a new way to get public exposure and found it a great way to increase sales of vinyl records.

In 1889, Louis Glass and his partner William S. Arnold, both managers of the Pacific Phonograph Co., invented the first coin-operated player in San Francisco, displaying it at the Palais Royale Saloon on November 23 that year. Known as the “nickel-in-the-slot machine,” the player included a coin operation feature on an Edison phonograph. It was limited, playing only a few selections of songs and without amplification. However, it was an instant success, raking in over $4,000 (the equivalent of about $120,249.23 today) in the first year alone, and inspiring the creation of different versions across the US. In no time, “phonograph parlors” with multiple nickel-in-the-slot phonographs spread across America and Europe.

As the machine’s reach and popularity increased, technological advancements were made. In 1905, John Gabel presented the Automatic Entertainer to the world. It had 24 song selections. In 1928, Justus P. Seeburg manufactured a multi-select jukebox called the audio phone, which had 8 separate turntables, allowing people to choose from 8 different records per turntable. When recording artists first crooned into microphones and cut records into vinyl, an aspiring inventor in a Chicago music store worked nights to build a box that would play both sides of the record. While the Blue Grass Boys played to sold-out audiences in the Grand Ole Opry, guys and gals danced the night away by playing their song over and over again on the jukebox at a local pub.

The jukebox took a hit when radio, a form of free entertainment, emerged in the 1920s, and the Great Depression hit in the 1930s. The sale of records saw a drastic dip as disposable income crashed. With the 1933 repeal of Prohibition, jukeboxes found new homes in taverns and, despite the lingering Great Depression, were thrust into their Golden Age as people got ready to live it up again. Four brands dominated the market: Wurlitzer, Seeburg, Rock-Ola, and AMI.

World War II put a pause on jukeboxes, but with the return to normalcy following the war, they came back stronger and flashier than ever. In 1946, Wurlitzer introduced the 1015, known as “the bubbler,” consisting of a cornucopia of colors and bubbling liquid tubes. Seeburg released the M100A Select-O-Matic in 1949, the first jukebox that could play 100 selections. The following year, Seeburg’s M100B became the first jukebox to use 45 RPM records. Up until that time, 78 RPM records reigned. In the 1950s, jukeboxes continued to dominate, not only played in taverns, but with the emergence of rock ‘n’ roll, they were adored by teenagers in diners and soda fountains. “Drop the coin right into the slot/You gotta hear something that’s really hot,” sang Chuck Berry in his 1957 classic, “School Days.”

Jukeboxes waned in the 1960s, because of many factors, including the rise in live music venues and the growth of DJs at clubs, the proliferation of transistor radios, and the continued popularity of television. Still, jukeboxes hung on, even if they didn’t retain their cultural clout. In the late 1980s, they shifted their format to compact discs, which became the norm in the 1990s and into the 2000s. Today, most times when you see a jukebox — usually in a bar — it is an internet jukebox, which can bring a catalog of the world’s music at a touch. With mobile apps, people can choose songs from their phones without even getting off their barstools.

In 2011, TouchTunes once again revolutionized in-venue entertainment with the launch of Virtuo, a multi-application platform designed to appeal a tech-savvy audience. The company also created National Jukebox Day, in recognition of the important role jukeboxes have played throughout history. They scheduled it on the day before Thanksgiving, a day when a lot of people gather at bars in their hometowns.

And just for nostalgia’s sake, here are the top 5 jukebox hits of all time:

1. Hound Dog, Elvis Presley (1956)

2. Crazy, Patsy Cline (1961)

3. Old Time Rock & Roll, Bob Seger (1979)

4. I Heard It Through the Grapevine, Marvin Gaye (1968)

5. Don’t Be Cruel, Elvis Presley (1956)

Want more good old jukebox music? Check out the Library of Congress’s Jukebox Day by Day (click here)

See what was recorded on any given day of the year. Check your birthday, an anniversary, or any other month and day of interest.

November 23: Fibonacci Day

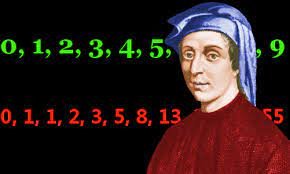

In the 12th century, Leonardo Bonacci invented a pattern of counting that continues to influence math and technology today. One of the most important mathematicians of the Middle Ages, Leonardo Bonacci — later known as Fibonacci, “the son of” Bonacci — invented a sequence of numbers that shows up constantly in nature, physics, and design.

Born to an Italian merchant in 1170, the young Leonardo traveled to North Africa with his father, where he was exposed to the Hindu-Arabic numeral system. The system, which includes zero and limits itself to 10 symbols, is much more agile and flexible compared to the unwieldy Roman numeral system. In 1202, Fibonacci published Liber Abaci. Written for tradesmen, it displayed the superiority of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system to the Roman numeral system and showed how the Hindu-Arabic system could be beneficial to Italian merchants for tasks like tracking profits, losses, and remaining loan balances. Also in this book, Fibonacci laid out what would much later become known as the Fibonacci sequence. Although he didn’t discover it — it can be found in ancient Sanskrit texts centuries before his time — he helped to popularize it, by being the first to introduce it to the Western world. He asked a question related to rabbits: “A certain man put a pair of rabbits in a place surrounded on all sides by a wall. How many pairs of rabbits can be produced from that pair in a year if it is supposed that every month each pair begets a new pair which from the second month on becomes productive?” The formula that is used to find that answer is the Fibonacci sequence, which can be used to calculate the proportions of countless things on Earth and beyond, such as animals, plants, weather patterns, and even galaxies.

Actually, beyond a small section in Liber Abaci, Fibonacci didn’t write further about the sequence, and it was rarely brought up by others until the 19th century. It was given the name “the Fibonacci sequence” by French mathematician Édouard Lucas in 1877. Today it is often spotted in nature, and has been referred to as “nature’s numbering system” or “nature’s universal rule.” Numerous plants have Fibonacci spirals in their leaves and petals, and pinecones and sunflower seeds have them. The sequence is also found in the shapes of hurricanes and galaxies, and even in music. It is commonly postulated that the nautilus seashell has it, but it does not; there are other similar claims that go too far. Still, we celebrate the sequence and many places it can be found today, on Fibonacci Day!

Fibonacci Day celebrates this important mathematician and provides an opportunity to marvel at the way math pervades everything around us. November 23 — or 11/23 — is the date of Fibonacci Day because the first series of numbers in the Fibonacci sequence are 1, 1, 2, and 3.

November 24: Flossing Day

Flossing Day is celebrated on the fourth Friday in November (i.e., the Friday after Thanksgiving), which, this year, is November 24. The holiday stresses the importance of flossing your teeth every day for excellent oral health. The American Dental Association recommends flossing at least once a day to achieve the best results for oral health. Daily flossing removes plaque from areas between teeth where a toothbrush is ineffective. Plaque can turn into calculus or tarter, so it’s important to floss daily. Flossing is also an important step in the prevention of gum disease and cavities.

Before written history, humans have used a wide variety of materials like dental floss. Based on anthropological evidence found in ancient humans, horsehair was one of the first types of dental floss. Toothpicks and chew sticks with sharpened points were also two of the early tools for interdental cleaning.

In 1815, Dr. Levi Spear Parmly, a New Orleans dentist, created the earliest iteration of the modern dental floss. It was a thin, waxen silk thread that he encouraged his patients to use. This thread was readily available everywhere because it was used in tailoring. Four years later, Dr. Parmly published “A Practical Guide to the Management of Teeth.” In the book, he recommended brushing twice a day and flossing once a day.

In 1882, the Codman and Shurtleff Company began producing unwaxed silk floss, marketed as dental floss. In 1898, Johnson & Johnson patented dental floss and began producing all types of waxed and unwaxed dental floss, using the same silk material as surgical stitches.

In the 1940s, silk became expensive because of WWII, causing the price of silk dental floss to skyrocket. Dr. Charles Bass introduced the idea of replacing silk with nylon. The idea received traction and later led to the invention of dental tape.

Dental floss has since evolved and now comes in different textures, materials, and flavors. They’re also made to fit different mouths’ shapes and sizes. In 2000, the National Flossing Council created Flossing Day to remind everyone of the importance of flossing.

November 25: National Parfait Day

National Parfait Day celebrates the parfait, a treat that originated in late 19th century France, and literally translates from the French to “perfect.” The history of parfait can be traced to the invention of a popular dish we all know (and count on): dessert. The word “dessert” is derived from the French word “desservir,” meaning “to clear the table.” And it all began with sugar.

In the Middle Ages, sugar was rare in Europe and was only enjoyed by the rich and aristocrats on special occasions. From that period to the late 15th century, refined sugar served as a sweetener and seasoner, sprinkled on stew and roasted meat. The dessert itself was fruit, gingerbread, sugared almonds, and jelly. Sometimes cookies, marzipan, or meringues were served as dessert. As time progressed, sweetening meals with sugar lost its appeal (thank you), and focus was placed on visual presentation. Chefs began crafting elaborate sculptures, entirely made of sugar, which served at the centerpiece of the dessert course. The industrial revolution transformed dessert from a meal for the elite to something easily accessible to the masses. During this time, the parfait emerged. One of the first parfait recipes dates back to the 1890s in France. As French culture spread outside its borders, European countries and the Americas adopted what was fashionable, including the parfait dessert.

Today there are 2 types of parfaits: the traditional French type and an Americanized version. Both types are eaten in the US. The traditional French parfait is a frozen dessert with a custard-like consistency, made up of eggs, cream, sugar syrup, and sometimes alcohol. The Americanized version is made in a variety of ways, usually served by layering its ingredients in a clear glass. Common ingredients that are layered include ice cream, parfait cream, flavored gelatin cream, yogurt, granola, nuts, and fresh fruit. The parfaits are often topped with whipped cream, liqueurs, and canned or fresh fruit. The more the parfait leans towards yogurt, fresh fruit, and nuts, the healthier it is.

Over the years, different variations were created, and now, parfait occupies a space in the American dessert culture. US restaurants and ice cream shops use ingredients such as parfait cream, ice cream, gelato, or pudding and layer them in a tall clear glass. To finish the parfait, a dollop of whipped cream is added or even fresh fruit or a drizzle of flavored liqueur.

The Northern US expanded the parfait, making it more of a healthy meal, using yogurt layered with nuts or granola or fresh fruits such as strawberries, blueberries, bananas, or peaches. The idea spread quickly across all parts of the country, and the yogurt parfait gained popularity as a breakfast item.

November 26: Good Grief Day

The world celebrates Good Grief Day to honor the life and the legacy of one of America’s most revered, legendary cartoonists: Charles M. Schulz. Schulz is best known for his “Peanuts” comic strip. His “stories” and characters have brought boundless delight across the globe. The fact that his characters — Snoopy, Charlie Brown, and the rest of the gang — have withstood the test of time demonstrates how influential these legendary characters have been worldwide.

Schulz was born on November 26, 1922, in Minneapolis, MN. His interest in the arts began in his childhood. He would spend his days taking in the works of Pablo Picasso, Edward Hopper, and Andrew Wyeth, while also developing a preference for cartooning. He would draw dozens upon dozens of cartoons, inspired by either the cartoons he admired or the world around him. At 15, he sent one of his drawings to the “Ripley’s Believe it or Not!” weekly column. It became his first published cartoon. He knew then that this was his life’s work.

From 1947 to 1950, Schulz's first comic strip, “Li’l Folks,” appeared in his hometown paper, the St. Paul Pioneer Press. He first used the name “Charlie Brown” in this comic, which also included a dog that looked similar to Snoopy. Li’l Folks was dropped in 1950, and Schulz took some of its best work to the United Feature Syndicate, which picked up his work. Similar to Li’l Folks, it introduced a set cast of characters. The syndicate came up with the title “Peanuts” for the strip, named after the peanut gallery from the Howdy Doody show. At its debut on October 2, 1950, Peanuts was printed in 9 newspapers as a daily strip. By its height in the 1960s, it was printed in over 2,600 newspapers.

Schulz’s creations have brought laughter and joy to millions around the world. But the strip went beyond chuckles. Peanuts was known for its complex humor, and for its psychological, sociological, and philosophical overtones. During its early years, Peanuts was ahead of its time in terms of its social commentary. Throughout the 1960s, Schulz used the comic strip to address racial and gender issues. He usually did this by creating narratives where equality, or at least the acceptance of different races and gender norms, was seen as natural. For example, Franklin, an African-American character, went to an integrated school, and his place there was unquestioned. Similarly, Peppermint Patty’s athletic ability and self-confidence were also not called into question, and Charlie Brown had girls on his baseball team. Schulz also addressed other social issues such as the Vietnam War, and children’s issues such as school dress codes. Religious themes were also often touched on, most memorably in the television special, “A Charlie Brown Christmas.” Introduced in 1965, it still runs in syndication today.

Charlie Brown quickly became Peanuts’ main character, known for his lack of self-confidence, but also his drive to not give up. Other early characters were Shermy and Patty (not Peppermint Patty, who arrived in 1966). Snoopy made his debut in the 3rd strip on October 4, 1950. Over time other characters were added, incuding Violet, Schroeder, Lucy, Linus, Pig-Pen, Sally, Frieda, Marcie, and Woodstock.

Over the years Peanuts has been adapted to many formats, including books, feature films, television films, theatre, and video games, and it is seen as one of the most influential comic strips of all time. Schulz received numerous accolades for Peanuts, including being inducted into the William Randolph Hearst Cartoon Hall of Fame, and receiving a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Peanuts has been called the second-best comic of all time by The Comics Journal (Krazy Kat was #1, Maus was #3). Furthermore, film adaptations of the comic have received Peabody and Emmy awards.

On January 3, 2000, the final daily Peanuts comic strip was published, although Schulz had drawn 5 extra Sunday comic strips that were soon published. The final new comic strip, which was similar to the January 3 strip, ran a day after Schulz's death.